|  |  |

|

| ||

|  |  |

|  |  |

|

| ||

|  |  |

|

|

Conscious of "a rumbling of thunder," thousands of people in the greater New York area rushed out into the streets, clad in pajamas or nightgowns. Still others held their ears, punished by a "deafening roar," while stepping gingerly in bare feet over fragmented window glass.

In Jersey City, where the skies were a saffron hue, one witness described the holocaust as an "American Verdun. Bombs soared into the air and burst a thousand feet above the harbor into terrible yellow. Shrapnel peppered the brick walls of the warehouses, plowed the planks of the pier and rained down upon the hissing waters."

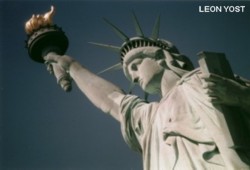

On Ellis Island, close by the scene of the blast, the Immigration Station was battered and pocked. Newly-arrived immigrants were led out of their dormitories only to be covered with hot cinders raining down from the heavans. On the same island, 90 whimpering patients were hastily removed from a government hospital for the insane.

The explosions, in diminishing key, kept up until dawn. It was not until Monday afternoon that the harbor area had calmed down and the last spirals of smoke had dissipated. Black Tom was gone completely. There wasn't a trace of the pier, the warehouses, the cars or locomotives, the barges or even of Black Tom Island itself. All were gone, reclaimed by the sullen, shallow waters of the bay.

No one could accurately assess the physical extent of the loss, or even set a price tag, though $20 million became a generally accepted guess. Loss of life, however, was singularly low: a railroad guard, a policeman and a child thrown from its crib in Jersey City. The fourth, whose body was washed ashore six weeks later, was the captain of the Johnson 17.

What had happened? An accident? One of the detectives admitted lighting the smudge pots. Two of them were immediately arrested, then released when it was realized that the pots were an unlikely trigger for the massive explosion.

Mrs. Rushnak, however, thought two and two made four. When the explosions finally subsided and dawn reddened the pall of smoke on the eastern horizon, she stepped cautiously out of bed, over the broken glass from every one of her windows, and tiptoed to Kristoff's room.

Se found him dressed, sitting on the edge of his bed, running and rerunning his fingers through his tossled shock of reddish hair, mumbling, "What I do? What I do?"

Mrs. Rushnak did not attempt to question him, but hurried to the home of Mrs. Chapman, her daughter. Together they called on old friend Captain John J. Rigney og the Bayonne Police, telling him of their suspicions. Mrs. Chapman recalled "he had s habit of going away from time to time, and everywhere he went there was an explosion." When he came home, he always seemed to have "plenty of money."

Once, the younger lady had found an opened letter in his room, written by Kristoff, addressed to so,eone named "Graentnor," demanding "more money."

Kristoff was arrested. H e told a semi-coherent story of working for a man named Graentnor, carrying suitcases for him. He thought these suitcases contained blueprints of factories and bridges, maybe books and money as well.

Investigators looked up Kristoff's background. He had been born in Slovakia, a subject of Austri-Hungary. H e came to America in 1899 and had worked at the Tidewater Oil Plant, near Black Tom, just before the explosion. He could offer no alibi for his whereabouts the night of the explosion. Even so, he was released as "insane but harmless."

He then enlistecl in the U.S. Army.

Soon, Americans everywhere were doing the same thing. Provocations, including the explosion, in January 1917, at a munitions plant at Kingsland, N.J., finally led to Uniteted States entry into the war in Europe.

Black Tom was overridden in the public mind bv greater concerns of the moment.

After the Armistice there were many corporations, primarily the Lehigh Valley Railroad, and individuals damaged by the Black Tom explosion and other disasters, who wanted redress, if possible. A Mixed Claims Commission, composed of one American, one German and an "umpire," was appointed to investigate all of the "incidents" prior to April 1917.

Black Tom's trail led, inescapably, back to Kristoff. Discharged from the Army, he was found in an Albany, N.Y,, jail, serving a sentence for theft. He admitted he had worked in the Germans' employ for "a few weeks," but offered nothing conclusive.

Released, he was followed until he turned up in jail again, for a minor offense. Ultimately, in 1928, the off-and-on pursuit of Kristoiff ended in a potter's field on Staten Island. There a corpse was exhumed, with papers identifying it as Kristoff. Teeth impressions failed, however, to match those in Army dental records. Was this or wasn't this Kristoff's body?

Other former German agents, among them Kurt Jahnke and Lothar Witzke, though now out of the country, were nonetheless located and questioned. The two, described as "one of the deadliest teams in history," had apparently done much of the work of actually secreting Rintelen's pencil bombs on outgoing ships.

Interviewed in South America (and later in China), Witzke was voluble enough since he was beyond the reach of any prosecution. Of course, he said, he "did the work in New Jersey with Jahnke when the munitions barges were blown up and the pier wrecked." He added that the two were nearly drowned bv the waves following the first blast.

Further investigation showed that two of the pier guards had been on the Germans' payroll and that Kristoff, an "intermediary,'' had asked them to relax their vigilance.

Not until 1930, however, did the case seem finally clinched when Paul Hilken, a naturalized American living in Baltimore, admitted having been "paymaster" for a number of German agents. One of them, "Graentnor," already alluded to by Kristoff, also used the name Max Hinch.

The trail that led to Hilken's confession was a damning message written in a copy of Blue Book magazine, of January 1917. The message was written in lemon juice, producing an ink that was invisible until heated.

The note was found on page 636, among the lines of the novelette, "The Yukon Trail." Citing Black Tom Terminal by name, the message told Hilken that "Kristoff, Wo1fgang and that Hoboken bunch" were to be paid, and was signed "Hinch." Hinch, or Graentnor, was a shadowy figure who was never found.

The Mixed Claims Commission decided, at last, that there must have been "foul play" behind the Black Tom explosion. Understandably, no one would ever, know whether it was actually Kristoff, Jahnke, Witzke, Graentnor, Hilken, one of the guards or posibly someone else who was the principal saboteur. Who lighted a fuse or tossed the first match or magnesium flare? The answer to this question was obviously at rest in one or more graves. The commission agreed, however, that $50 million, the greatest amount of damages in history for a case of this kind, should be apportioned among the plaintiffs.

Yet, it was not until 1939 that the awards were actually made -- when the Germans, under even worse leadership, were again upsetting the world's status quo. There would be trouble once again in the United States, but this time, at least, no Black Toms.

Your Ancestors' Story |

Bruce Springsteen's Jersey Shore Rock Haven! |

|

UrbanTimes.com |